Oxidative Stress: What It Really Means for Your Health

You may have come across the term oxidative stress in a test result, a podcast, or an article about ageing, inflammation, or chronic disease — often without much explanation. It can sound worrying, especially when it’s linked to damage, disease, or decline.

If you’re trying to know about oxidative stress and what it actually means for human health, you’re not alone. Many people are left uncertain about whether oxidative stress affects their body in a serious way, or whether it’s simply another medical term used without enough context.

Let’s slow things down and explain it clearly.

Oxidative stress in simple terms

Oxidative stress is fundamentally about imbalance.

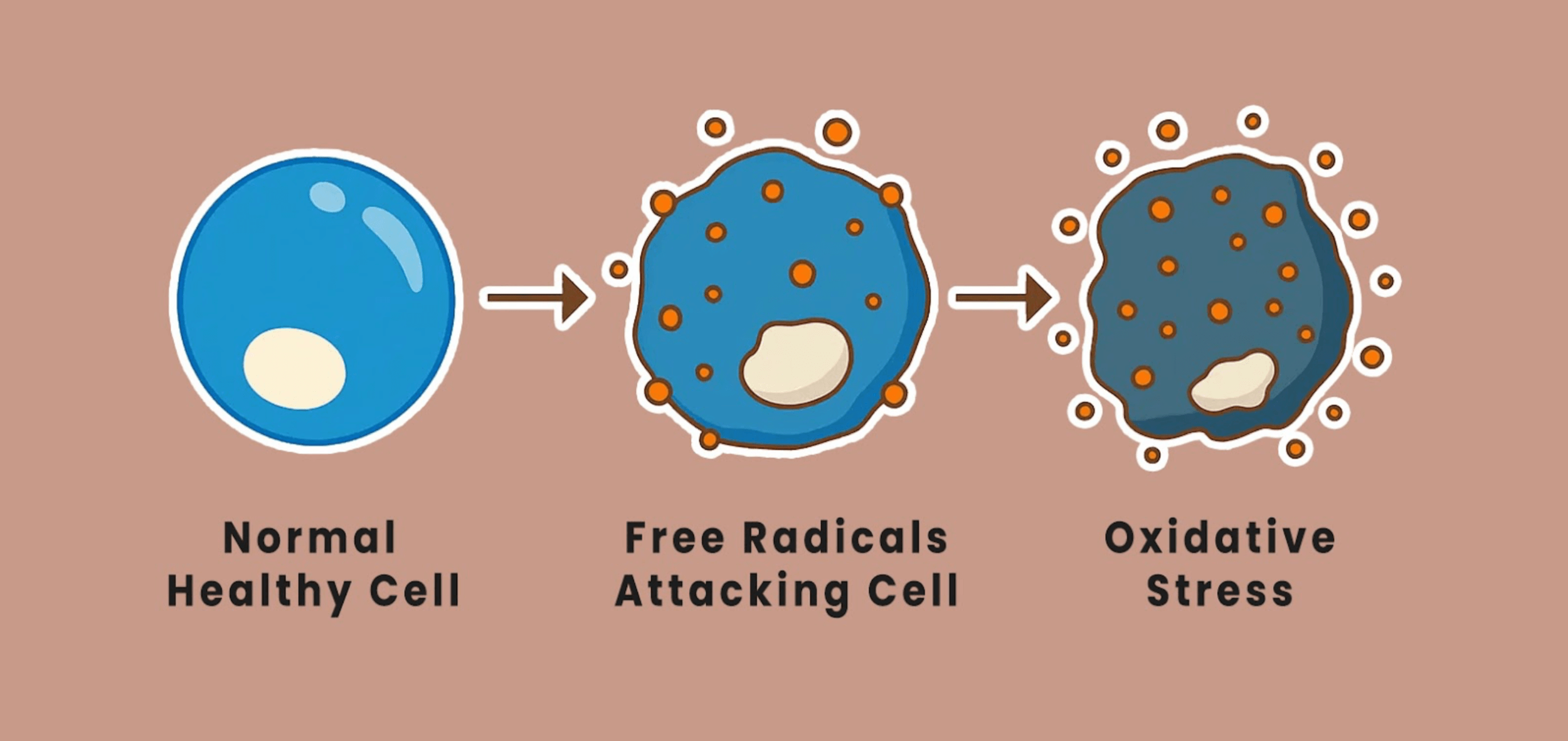

Your body constantly produces energy through normal processes such as oxidative metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation. As part of this, it creates unstable molecules known as free radicals, also called reactive oxygen species.

A free radical is a molecule missing an electron, which makes it reactive. These molecules aren’t automatically harmful - they play an important role in immune defence and cell signalling.

Problems arise when free radicals accumulate faster than the body’s protective systems can manage.

That state is called oxidative stress.

Put simply, oxidative stress is an imbalance between free radical production and the body’s ability to control them using antioxidant systems.

The role of antioxidants in the body

An antioxidant is a substance that helps stabilise free radicals by donating an electron, reducing the chance of damage caused by oxidation.

Your body is not passive in this process. It can:

Prouce antioxidants internally

Recycle antioxidants after use

Obtain antioxidants from dietary sources

This network of antioxidants in your body works continuously to protect cells and tissues. Oxidative stress develops when this system is under sustained pressure - not because antioxidants are absent, but because demand exceeds capacity.

This is why free radicals and antioxidants are best understood as a dynamic system, not opposing forces.

Effects of oxidative stress on the body

When oxidative stress persists over time, it can begin to influence how different systems in the body function.

1. Cellular effects

At a cellular level, excess free radicals may interfere with DNA, proteins, and fats, subtly disrupting normal cell function. As this kind of oxidative damage accumulates, it can place increasing strain on the body’s usual repair processes.

2. Ageing processes

Oxidative stress is involved in aspects of the ageing process. Free radicals can affect collagen and elastin — the proteins that help maintain skin structure and elasticity - and similar changes may influence how tissues and organs age more broadly over time.

3. Cardiovascular health

Within the cardiovascular system, oxidative stress can affect the lining of blood vessels, contributing to plaque formation in the arteries. Over time, this may play a role in conditions such as high blood pressure, heart disease, and stroke, particularly alongside other risk factors.

4. Metabolic health

Oxidative stress may interfere with insulin signalling, increasing the likelihood of insulin resistance. In people living with diabetes, higher oxidative stress is also associated with an increased risk of complications affecting nerves, kidneys, and vision.

5. Brain and neurological health

The brain is especially sensitive to oxidative stress due to its high energy demands and relatively lower antioxidant defences. For this reason, oxidative stress has been linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, where it may contribute to disease progression rather than act as a single cause.

6. Inflammation and immune balance

Oxidative stress and inflammation often reinforce one another. When oxidative stress remains unresolved, it can help maintain a state of low-grade chronic inflammation, which is commonly seen in long-term conditions such as arthritis, asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, and ongoing tissue irritation.

This is why oxidative stress is often discussed in relation to ageing, heart disease, diabetes, and cancer - not as a single cause, but as part of the biological environment in which these conditions develop.

External factors that increase oxidative stress

Oxidative stress rarely has a single source. More often, it reflects cumulative load across multiple systems.

Common contributors include:

Ongoing psychological or physical stress

Poor sleep or disrupted circadian rhythms

Metabolic strain and blood sugar instability

Environmental exposures such as pollution, smoking, and excess alcohol

Periods of illness, infection, or prolonged recovery

These factors can increase free radical production or reduce the body’s ability to neutralise them, gradually tipping the balance toward oxidative stress. Importantly, this is not a sign of personal failure — it reflects how responsive human biology is to its environment.

Oxidative stress and disease: what the links really mean

You may see oxidative stress mentioned alongside a wide range of conditions, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurological disorders. This can feel alarming, but the relationship is more nuanced.

Research suggests oxidative stress is involved - rather than solely causative - in:

Cardiovascular disease and heart disease, including plaque formation

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis

Certain cancers, including lung cancer and prostate cancer

In cancer research, oxidative stress may influence DNA damage, cancer cell behaviour, immune response, and disease progression. At the same time, oxidative stress is also involved in cancer treatment and normal immune defence, which highlights how context-dependent it is.

This is why oxidative stress appears in discussions about both disease and cancer prevention - without being treated as something that can or should be eliminated entirely.

Diet, antioxidants, and prevention

A diet that naturally supports antioxidant systems can help protect against oxidative stress over time.

This usually means eating a variety of fruits and vegetables, whole foods, and dietary sources that are naturally rich in antioxidants. These work alongside the body’s internal defences rather than overriding them.

By contrast, antioxidant supplements are not always helpful and may, in some situations, interfere with the body’s normal signalling and repair processes. For this reason, antioxidant treatment is not one-size-fits-all and is best considered in context.

Can you reduce oxidative stress?

Rather than targeting oxidative stress directly, most clinically grounded approaches focus on supporting the systems that keep it in balance.

1. Supporting antioxidant intake through food

Eating a diet that includes fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds helps support the body’s existing antioxidant defences without overwhelming them.

2. Reducing exposures that increase oxidative load

Stopping smoking and keeping alcohol intake within moderate limits can reduce free radical production and overall oxidative burden.

3. Finding a sustainable approach to movement

Moderate, consistent physical activity supports metabolic health and strengthens the body’s own antioxidant systems, without the strain associated with overtraining.

4. Eating in a way that supports balance

Limiting highly processed foods and excess sugar while prioritising whole grains, lean proteins, healthy fats, and fibre supports steady energy production and cellular repair.

5. Prioritising sleep and recovery

Sleep is one of the body’s most important repair windows. During rest, oxidative injury repair, hormone regulation, and immune balance all take place.

The aim is not to eliminate oxidative stress, but to help the body manage it more effectively.

When support may be helpful

For some people, concerns about oxidative stress arise alongside ongoing symptoms, slow recovery, or confusing test results. In these situations, reassurance often comes from understanding the broader picture rather than focusing on a single marker.

A functional approach can help by:

Exploring how stress, sleep, nutrition, inflammation, and recovery interact

Using testing selectively and interpreting results in context

Identifying patterns across systems rather than isolated abnormalities

This kind of support focuses on education, orientation, and resilience — not quick fixes or over-treatment.

A calmer way to think about oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is not a diagnosis or a verdict on your health. It reflects how your body is responding to demand, load, and recovery over time.

For many people, understanding oxidative stress brings relief rather than fear. It offers language for experiences that feel real but hard to explain - without suggesting something is irreversibly wrong.

Balance in the body is not about perfection. It’s about capacity, adaptation, and repair.

Clarity - not urgency - is the most helpful place to begin.